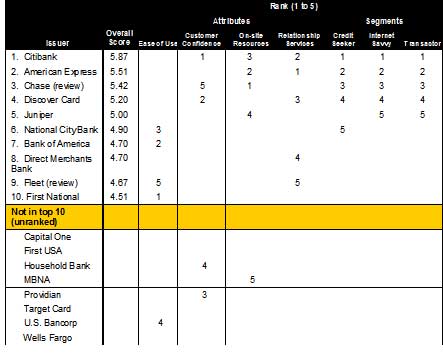

UBS Wealth Management US last week launched a new payments-card package for its brokerage customers that among other things cleverly turns an ordinary American Express card into what amounts to a debit card. The program was created for UBS by Barclay’s PLC’s Juniper Bank unit.

The whole idea is to bind its customers to the U.S. brokerage unit of Zurich-based UBS by giving them a payments-card package that the firm hopes will be their primary spending vehicle, says Peter Stanton, executive director of the UBS unit’s Banking Strategy Group. It’s not an effort to enter the very tight U.S. credit card business

“It’s definitely not our intention to be another credit card provider,” he says. “This is a consolidation strategy; it’s all connected to our role as their primary wealth-management advisor, and ties them closer to us because of the services we provide.”

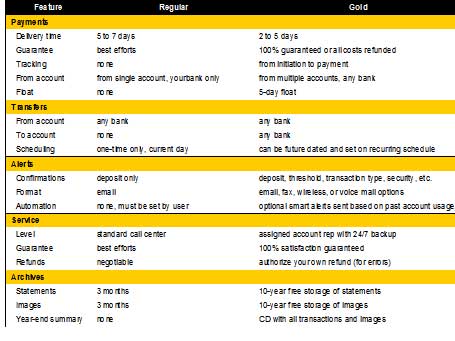

On the surface, the package is an ordinary Visa credit card and an ordinary American Express charge card, bundled with a very extravagant rewards program that offers cardholders enticements like jet fighter rides or a sleepover at FAO Schwartz. Rewards run from one point to 1.5 points per dollar spent, depending on whether the customer chooses the basic “Select” Visa card or one of the more elite Visa cards that carry annual membership fees of up to $1,500. UBS says it has about 15,000 such accounts.

By offering its brokerage customers such payment packages, UBS joins a widening club of brokerage companies trying to retain customers whose loyalty is mercurial at best. “With acquisition costs so high, and turnover very high also, the emphasis has been to keep the customers they already paid for, happy,” says Ariana-Michele Moore, a senior analyst with Celent Communications.

The Amex card allowed UBS and Juniper to create a vehicle that functions like a debit card from the user’s perspective—UBS calls the card a “delayed debit card,” though Amex insists that the cards are ordinary Amex cards—while earning the issuer the much higher American Express interchange fees.

It does this by an interesting sleight of hand that seems to be built around the fact that none of the parties to the deal care what the card is called, as long as they get what they want from it. Cardholders use the Amex card like an ordinary debit card, including being able to use it to withdraw surcharge-free cash at ATMs that accept Amex cards. At the end of the month, their central brokerage account, or RMA (resource management account), is automatically debited, and no bill is sent to the customer. Purchases are limited to the funds available.

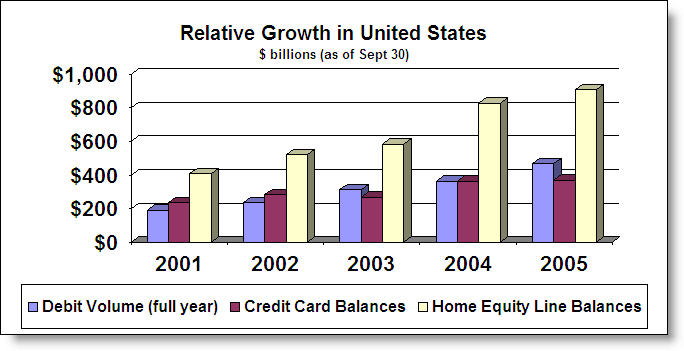

This way, UBS gets what amounts to a debit card for its customers, while Amex and Juniper get full price for an Amex card. And as an added bonus, Juniper gets a piece of the debit card market, which is quickly overtaking credit cards as the payment vehicle of choice in the United States.

How the parties came up with this deal is unknown. UBS’ Stanton says his shop approached Juniper around August of 2004 as part of a typical RFP process, and went to contract last April. Juniper refused any comment on the matter, referring all questions to UBS.

“It has in-between functionality,” says Stanton. “It functions as a debit in the sense that it accesses your available funds; it functions as a charge card because the charges accrue, and instead of having to make some sort of payment, the payment is automatic.” The idea, he adds, was to allow purchases to be made without interfering with a client’s trading accounts.

All in all, it’s a smart deal, says Celent's Moore—among other things, because people with brokerage accounts are typically wealthier, and travel overseas, so that the package gives UBS clients a secure spending vehicle.

“It’s all about providing flexibility to their brokerage customers, but it could also be enticement for people considering opening a UBS account—it could be the thing that tips the scale,” she says. (Contact: UBS Wealth Management US, 212-882-5698; Celent Communications, Ariana-Michele Moore, 503-617-6112)