People have grown wary of credit cards. They’re paying them off faster; generally, debit cards are edging them out as payment vehicles. And at least for now, home equity loans are increasingly more popular than credit cards among consumers (click on inset for more details and see tables below).

People have grown wary of credit cards. They’re paying them off faster; generally, debit cards are edging them out as payment vehicles. And at least for now, home equity loans are increasingly more popular than credit cards among consumers (click on inset for more details and see tables below).

The result? Credit card portfolios are losing profitability, even though net losses and delinquencies are down, and serious questions about the industry’s future are surfacing. So are questions about how wise banks were when they snapped up most of the monoline credit card operations last year. The business model needs an overhaul, says observers, but so far, issuers are just changing the oil. And there may be no way out.

The problem can’t be solved by boosting fees and adjusting annual percentage rates (APRs), say observers. In fact, it’s the recent inclination of issuers to plaster their card holders with unexpected fees and higher APRs—often over behavior unconnected to the account in question—that’s caused cardholders to begin planning to cut their outstanding card account balances, and the number of cards they hold: According to the most recent Experian-Gallup Personal Credit Index, 65 percent of respondents said they’re planning to pay down their card balances this year, and 35 percent said they plan to drop at least one card.

Those plans are up 14 percent from last year, according to Dennis Jacobe, The Gallup Organization’s chief economist. “The issues going forward are higher minimum payments, which has implications for future consumer usage,” he says. “Consumer sentiment is relatively negative in terms of consumer card debt: So credit card use is going to stay flat, and all the growth [in consumer credit] will be in something else.” That something else will probably be home equity loans, which, Jacobe points out, are a superior credit product from a consumer’s perspective, and a phenomenon unlikely to disappear unless housing prices collapse.

Jacobe adds that in the past few years, issuers have actually been hurting their own credit card revenues. “It’s my belief that the aggressive behavior of financial institutions relative to home equity loans has cannibalized their own credit card stuff,” he says. “It’s really hard to assume that credit card debt is going to stay the same, when the banks are promoting home equity loans that have the same features as credit cards, at a much cheaper rate.”

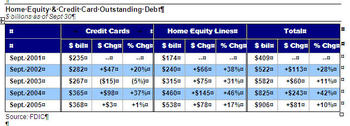

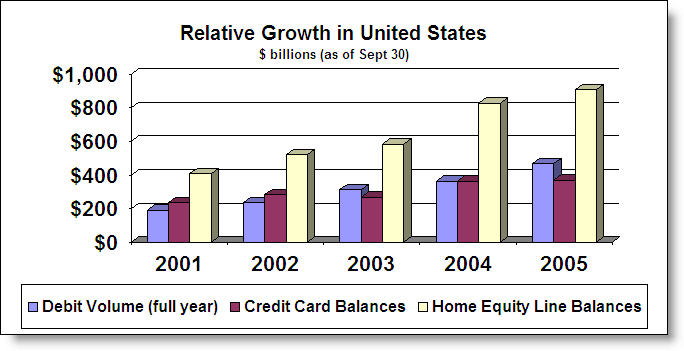

The data certainly bears Jacobe out: Between 2001 and 2005, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. says outstanding balances of home equity loans grew from $174 billion to $538 billion, while outstanding credit card loan balances in the same period only grew from $235 billion to $368 billion (click on chart above for details). Credit card portfolio profitability, meanwhile, has been falling—from a portfolio-wide yield on equity of 2.52 percent in 2002, to 1.86 percent in 2005, according to the Federal Financial Institution Examination Council. This, despite the fact that the same data show that net credit card losses fell from 0.39 percent of the overall portfolio in 2002, to 0.17 percent in 2005, while credit card delinquencies fell in the period from .08 percent to .04 percent.

Much consumer spending, meanwhile, has migrated from credit cards to debit cards: From 2001 to 2005, Visa’s total debit card payment volumes, online and off, grew from $190 billion to $467 billion (click on chart above for details). MasterCard, which hasn’t published a 2001 to 2005 debit data series, likewise didn’t publish its online debit card data with its most recent results. MasterCard’s 2005 offline purchase volumes were $117 billion, compared with Visa’s $375 billion.

Data like that have led credit card experts like John Gould, a partner in Prepaid Advisory LLC, to urge card issuers to change their thinking.

“As a standalone business, credit cards are no longer viable,” he says. “Even MBNA, which was very successful, realized they could not grow the business sufficiently to be able return growth and shareholder value. It’s why they sold it. It’s not that it became unprofitable, but they could no longer grow the business.”

Of course, credit card executives, a typically hard-headed lot, aren’t lost in Fantasyland when it comes to the future of their business. They know the underlying fundamentals of the business are changing, and that they’re going to have to change along with it. But that won’t be easy, says Gould.

“My view is that between the growth of the cost of funds, which dampens your spreads, and increasing penalties and APRs, charge offs will increase, spending will be dampened, and they’ll be burned by the cost side of the equation, more than by the revenue side,” he says.

“But what the banks are doing about the fact that receivables have not been growing for the past five years is adjusting by becoming more reliant on interchange and penalty fees,” both of which are likely to be brought down by various pressures, he says. Looking forward, “The question is how sustainable is that model over a long term? It’s a lending product, not a transactional product, which to me is the fundamental problem; today, 41 percent of the people are convenience users and pay their bill off each month. And if you’re a convenience user, by and large the issuer is losing money on you.”

Gould’s answer, not always well-received in banking circles, is to raise annual fees, much as has American Express. And, he adds, issuers should pay more attention to the profitability of each card, instead of counting each outstanding card as a plus. “If you think about the cost to acquire a new account, which is somewhere above $150 an account, and you realize that four out of ten accounts are never activated, then you can see that most of those cards are an expense, and not an asset,” he says.

“At the end of the day, they’re going to have to re-price the product. All the other things they’re doing are short-term fixes, not long-term solutions,” he adds.

All of which raises the question of how smart Washington Mutual, Bank of America, Barclay’s Bank and HSBC were last year when they more or less extinguished the monoline credit card bank model by buying Providian, MBNA, Juniper Bank and Metris, respectively. None of those deals were cheap, aside from Metris, and some, like Providian, were considered pricey at the time. “A lot of those decisions were based on past history, not on any future projections,” says Jacobe.

The other big problem for the issuers—not only the above banks, but also J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Citigroup, Wells Fargo & Co. and U.S. Bank, among others—is that interchange, the second major revenue stream from credit cards besides interest, faces a serious legal challenge, and is unlikely to stay at anything like its current level going forward. Combined with a decline in outstanding debt levels, and rising debit card use, the entire business model is under pressure.

Its probable savior? Human nature and cultural norms. America is a consumer nation: It’s been decades since this country’s consumers gave anything but lip service to actually exercising financial discipline, and last year we actually had a negative savings rate. While some of the blame can be laid at the door of falling real wages and rising living costs, some of the blame also goes to an apparently bottomless hunger for iPods, plasma televisions, and other must-have consumer items.

The data bear this out. In the past few years, says John Bartko, Standard & Poor’s’ head banking equity analyst, the trend has been for consumers to tap their home equity, pay down their credit cards—and plunge right back in. “We saw the funding of the credit card lines with the home equity loans, followed by a ramping up of their credit card debt,” he says. To the extent that consumers will be exercise any spending discipline now, he says, “That’s really been prompted by the increase in credit card rates, moving against them.”

That said, Bartko is no bull about the future of the credit card business. He says inroads into the core business made by home equity loans and debit cards have turned a money machine into another mature industry, grinding out inches on the ground.

Capital One is a perfect example of this, he says. Even with last year’s acquisition of Hibernia Bank, Capital One is pretty much a pure industry play, albeit one that also makes car and home equity loans. Chairman Richard Fairbank has been telling investors for the past few years, says Bartko, that Capital One’s go-go years are gone.

“Three years ago, he came out and said ‘We’ve been a high-growth company and managed ourselves as a growth company, but guess what? That train is coming into the station; this company is maturing, and the overall market is maturing,’” says Bartko. “And if you fast-forward to today, his mantra is that credit cards will always be a big part of Capital One’s business, but you won’t be seeing those double-digit growth numbers you saw a few years back—that growth from credit cards will be in the mid-single digit to 10 percent range, and the growth in the company will be coming from its other businesses.”

As for the big bank issuers? “It’s going to be much more of a challenge than it’s ever been before,” he says. “The competitive landscape is at least as intense as it’s ever been, and it’s probably going to get worse. And receivables growth will be falling. Absolutely.” (Contact: Prepaid Advisory, John Gould, 617-671-1150; The Gallup Organization, Dennis Jacobe, 704-639-9788; Standard & Poor’s John Bartko, 212-438-7368)